Latest Post

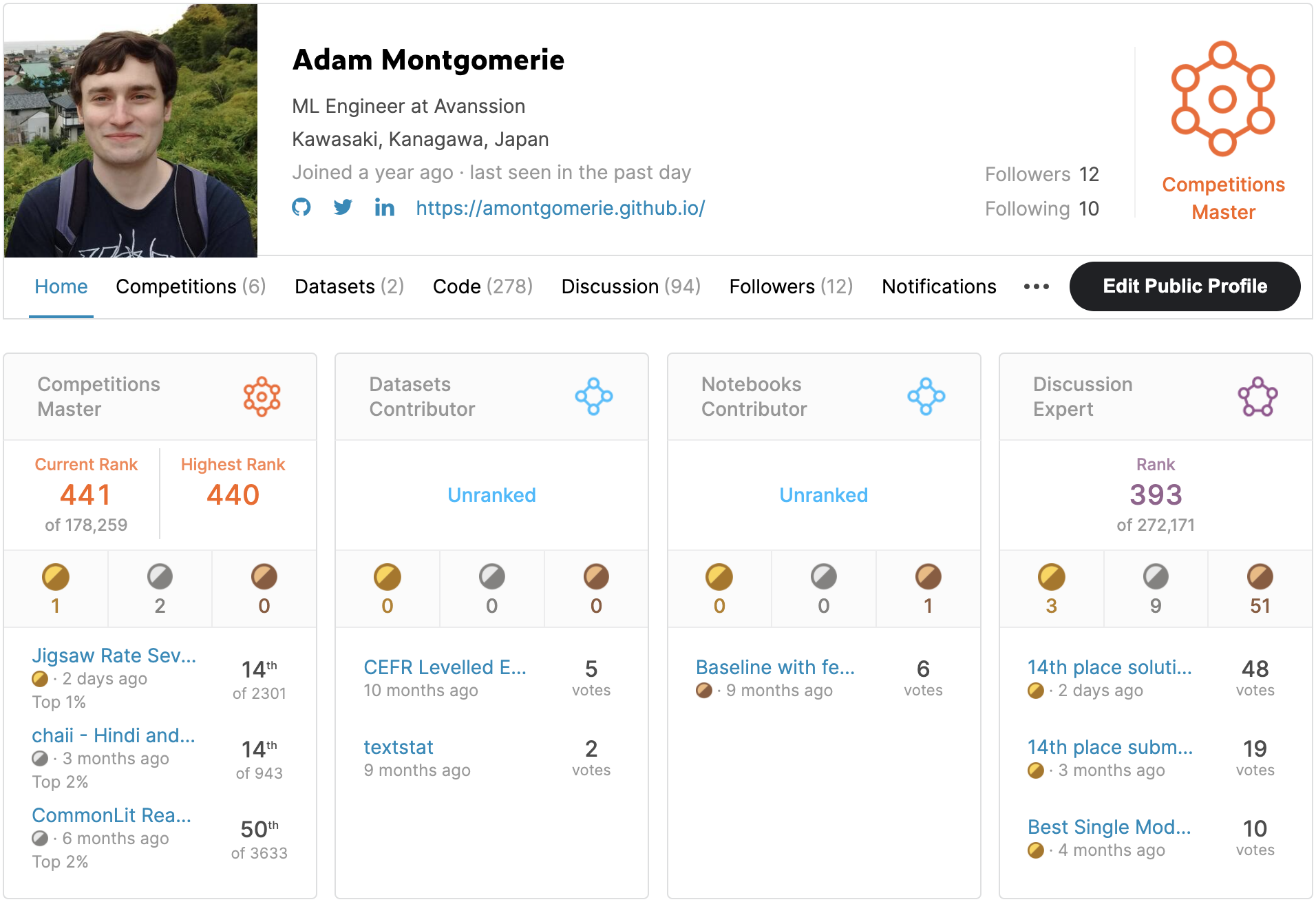

Kaggle Journey to Competitions Master

UPDATE: I did an interview with Sanyam Bhutani about my Kaggle journey on his Chai Time Podcast on Weights & Biases here

First Attempts at Competitions

I started entering Kaggle competitions near the start of 2021 (about 11 months ago as of the time of writing). I had previously been working on a few machine learning side projects (which I’ve written about on this blog before), but since starting to work full-time as an ML engineer I found that I didn’t really have the time or energy to devote to working on a full machine learning project lifecycle, in addition to doing the same at my job. Despite this, I still wanted to work on some more NLP projects since my work was mostly related to dealing with tabular data and recommender systems at the time.

I thought that Kaggle would be a good way to try out some of the new transformer architectures I’d been hearing about, without having to collect and label my own data, or having to deploy and maintain a whole system. I initially tried a couple of the monthly Tabular Playground series of competitions, which got me used to the format of a Kaggle competition. The first NLP competition I tried was the Coleridge Initiative competition, which turned out to be quite a difficult task with a strange leaderboard: it was possible to get a high public leaderboard score with a simple string matching function, but this didn’t translate to the private leaderboard at all. I gave up on this competition after working on it for a few weeks from lack of motivation.

CommonLit Readability Prize

Instead, I returned to working on my own projects. I built a CEFR classifier for predicting the reading complexity of texts for people learning English as a second language. Near the end of this project, I came across the CommonLit Readability Prize on Kaggle. This really got my attention, as it was almost the same task as I was working on by myself! Conceptually the only difference was that, while my project was aimed at people learning English as a second language, the CommonLit competition was focused on predicting the readability in terms of American grade school reading levels. Another difference was that the task was framed as a regression problem: we had to predict a real value for each text. My project had been a classification task, where I tried to map each text to a discrete reading level label.

I thought I might have better luck with CommonLit than I did with the Coleridge Initiative competition, so I started trying to translate some of my previous work into something that could be submitted to the competition. I quickly found that my hand-crafted features weren’t very useful, and contrary to my results in my own project, BERT-style transformers were definitely the way to go in the competition.

I managed to get pretty high up the leaderboard early on, and as the competition reached its final month I started getting some invites to merge teams. At first, I didn’t really want to, as I thought I might be able to get a competition medal by myself. However as the competition got closer to the end, I found my position on the leaderboard falling as merged teams started to overtake me. (Note: I didn’t realise at the time but I was actually kind of overfitting the public leaderboard at this point, so even if I had stayed near the top of the public leaderboard, I certainly would’ve lost a lot of places in a shake-up at the end).

Fortunately, I got another invite to join a team, which I accepted. Amazingly, I had stumbled into a team with three high ranked Kagglers who were all very experienced in competitions. When they asked me to share my work so far, I was embarrassed as my experiment tracking was a complete mess. I basically just had a big spreadsheet with a bunch of missing parameters, making it very difficult to reproduce what I’d done. On top of this, my naive attempts at ensembling were full of leaks.

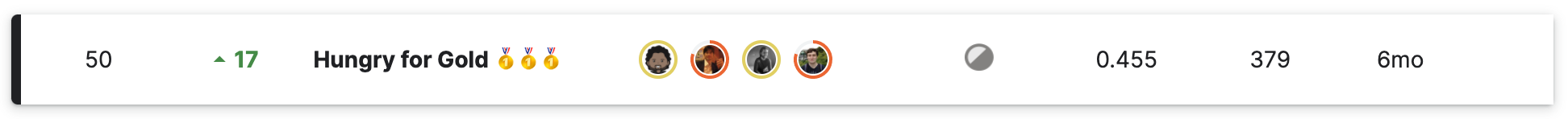

I tried to quickly get myself organised and learn as much from my teammates as possible. In the end we finished in 50th place with a silver medal, which I was pretty happy with. After that, I was hooked on taking part in more competitions. I realised I only needed one more medal to Competitions Expert rank, and then if I could somehow get a gold medal I wasn’t even that far off Competitions Master.

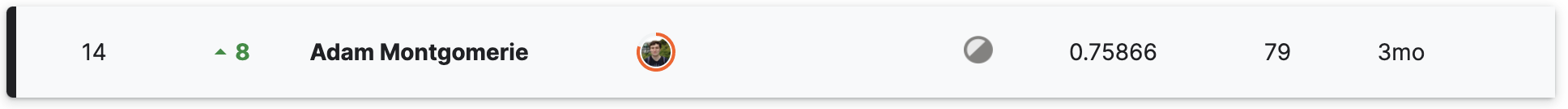

Chaii - Hindi and Tamil Question Answering

The second competition I worked on was the chaii - Hindi and Tamil Question Answering competition. Although I don’t speak any Hindi or Tamil, I’m interested in multi-lingual NLP, as it seems like there’s a lot of potential to use it to build systems to help people learn foreign languages. I had previously worked on a question generation project, but had never done extractive question answering, despite it being a standard NLP task. I tried to take everything I’d learned from the previous competition to organise myself better, which paid off as I was able to finish in 14th place and get another silver medal.

In the chaii competition, I had narrowly missed out on a gold medal by selecting the wrong submissions at the end of the competition. In most Kaggle competitions, you’re allowed to select two submissions at the end, and your final rank is whichever of the two performs best on the private leaderboard which is revealed at the end of the competition. Despite having a submission with a high cross-validation score, I hadn’t chosen it as one of my two final submissions, because it hadn’t performed so well on the public leaderboard, which at the time I was myopically focused on. This shook me out of my public leaderboard obsession. I realised that the old Kaggle mantra of “Trust Your CV” does hold important advice, so I resolved that in the next competition I would trust my CV no matter what. (Note: CV stands for Cross-Validation in this context).

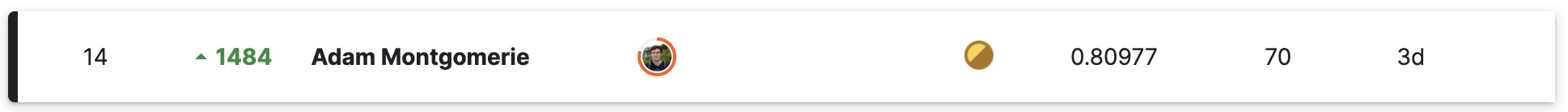

Jigsaw Rate Severity of Toxic Comments

The next competition turned out to be a real test of faith in this regard. I entered the Jigsaw Rate Severity of Toxic Comments competition. There were several strange things about this competition. The first strange thing was that there was no training data: instead we were expected to use data from previous Jigsaw competitions, or other public data we could find. The second strange thing was that the public leaderboard was only five percent of the total test data (making it potentially not a very representative sample of the overall set). The only other tool we were given was a validation set that was about three times the size of the public leaderboard, or fifteen percent of the size of the test data. The task in this competition was to match annotators’ rankings of pairs of comments in terms of which comment was considered “more toxic”. This leads to the third strange thing, which was that, since each pair of comments was shown to multiple annotators, and since duplicate annotations weren’t aggregated in any way, the test and validation sets contained conflicting labels, making it impossible even in theory to perfectly match all the annotators labels with predictions.

After making a few submissions, it quickly became clear that the public leaderboard and validation sets didn’t agree very well. Simply encoding some texts with TF-IDF and fitting a linear regression to predict their target values performed surprisingly well on the public leaderboard, even better than state of the art transformer networks. This trend didn’t translate to the validation set though. Here the results came out as I originally expected: transformers like RoBERTa outperformed any other type of model you could throw at the problem. Since I had already vowed to trust my CV, it was a fairly easy choice initially to ignore the leaderboard and stick to my local validation scores. My faith was increasingly tested however, as many other competitors got increasingly high on the leaderboard, dropping me down to one thousand five hundred and somethingth place.

The discussion forums were full of people speculating about why ridge regression might be better than BERT on this particular problem, which seemed to me to be the wrong question. This question already assumed that ridge regression was better, without investigating the lack of correlation between leaderboard and validation. The real question from my perspective was why did submissions which only got about sixty seven percent agreement with annotators on the validation set get ninety percent or more on the leaderboard.

As you might expect, there was a big shake-up at the end of the competition, where I was lucky enough to jump up to fourteenth place (again), barely getting a gold medal this time. Now with a gold and two silvers, I had reached the rank of Competitions Master.

Lessons Learned

I think I’ve learned a lot from taking part in Kaggle Competitions over the past year. I’ve seen people make the claim that Kaggle Competitions aren’t good preparation for “real-life machine learning” because you don’t have to collect, clean, or label data, or deploy or monitor the resulting system. While it’s true that you don’t have to do these things, there’s still a huge amount you can learn from Kaggle Competitions.

Experiment Tracking

When I started out with my first competitions, I didn’t realise I was going to be running hundreds of experiments over a period of several months. I found that without a solid system in place, it quickly becomes an unreproducible mess of metrics, data, and model weights. Small things like a consistent naming convention and file structure are important.

I’ve also learned the value of experiment tracking software like Weights & Biases which allow you to log hyperparameters and metrics from your training runs, and automatically generates plots. Compared to manually entering all the hyperparameters for every run, this is a significant time-saver. Not having to write data visualisation code to plot your training and validation metrics is really nice too.

Model Validation

Beyond simply learning to Trust My CV, I’ve learned the importance of building a CV scheme that is worth trusting. People often get tripped up by incorrectly calculating a metric, or by splitting their data in a way that leaks between folds, leading to a CV that should not be trusted.

I’ve also learned that not only public leaderboard leaderboards, but also validation folds can be overfit: for example if you evaluate every epoch or n steps with early stopping on each fold, you’ll end up with an unrealistic CV score. Say your early stopping condition causes fold 0 to stop on the second epoch, and fold 1 to stop on the fifth epoch, then which one is best? We can’t compare the score between folds, and we don’t know if, in general, our model should be trained for more or fewer epochs on this dataset. A more robust method is to calculate the CV across folds at each epoch, and then take the checkpoint for all folds at the epoch which performs the best on average. This advice comes originally from Ahmet Erdem and several other Kaggle Grand Masters.

Ensembling

Unlike the previous two points, this is something that I haven’t yet used outside of Kaggle (at least in the context of deep learning models). In a Kaggle competition it makes sense to blend or stack as many models as you can as long as performance on a key metric continues to improve, and as long as the final inference run time is within the competition’s maximum runtime allowance. In industrial machine learning applications, performance on a specific metric is not the only consideration, and is often not the most important one. We also have to consider other factors like inference speed, and server and GPU running costs. Despite this, I think it’s still worth mentioning here because it’s quite important in Kaggle Competitions, and because it could have occasional use in real-world scenarios.

The simplest ensembling techniques are just taking the mean of the outputs of several models to get a more accurate output. This technique is surprisingly consistent at improving scores. In cases where a mean doesn’t make sense, for example classification tasks, we can use another technique like majority voting instead. More advanced ensembling techniques include weighting each model in the ensemble differently when calculating the mean, and stacking models by taking the outputs of a set of models, and using them as input to another model.

You have to be careful when evaluating ensembles, as you can’t use the same data that you used to train the models. For stacking, this means you have to set aside a subset of the data that you don’t include in your CV folds. In other cases, you can round this by generating a set of OOF (Out Of Fold) predictions for each k-fold set of models. For each k-fold set of models, each model only generates predictions on the subset of data that was used to evaluate it, and which it didn’t see during training. This allows you to generate one prediction per example in the dataset. These OOF predictions can then be combined in different ways and averaged to optimise your ensemble’s overall score.

Recently, I’ve started using Optuna for finding model weights in an ensemble. I think this was the key factor that pushed my final score up from a silver to a gold in the Jigsaw competition.

Conclusion

I think most of the ideas here are things that many Kagglers or Data Scientists would say that they knew already, but I also think there’s a difference between knowing something in theory and being able to apply it in practice. If you don’t try it out, and mess it up a few times, you won’t be able to apply it properly when it’s really needed. Kaggle is a safe space to make mistakes: it’s better to have a data leak and broken model validation in a Kaggle competition than when deploying a model to production that’s going to serve predictions to thousands of paying customers.

I already knew what model validation, experiment tracking, and ensembling were before I entered any Kaggle Competitions, but I still made a dog’s dinner of it the first time I tried to put these ideas into practice my myself.

Posts

-

Kaggle Journey to Competitions Master

-

Jigsaw Rate Severity of Toxic Comments 14th Place Solution

-

Predicting the CEFR Level of English Texts

-

Token Classification With Subword Tokenizers for Bulgarian

-

Classifying Heavy Metal Subgenres with Mel-spectrograms

-

Using Spotipy to Collect Track Data

-

Generating Questions Using Transformers

subscribe via RSS